Adoption Needs Media, but Legal Media is a Problem

Or, Why you’ve been around forever but no one’s heard of you.

Does anyone care that your company exists?

Of course—you care. Your employees care, your investors care, and a few tinkerers with law blawgs care. If you’re in the early days, that may be it, and that may be right on schedule.

But driving attention to your solution isn’t simply a matter of time. According to research, you have buttons to push that get the kind of attention that leads to adoption. Pushing those buttons just may not look the way you think.

Here’s why:

Media drives adoption,

Legal lacks centralized media sources, so

You’re gonna have to create your own media, at scale, that triggers social networks.

We’ll dig into all that, but selling to lawyers begins with understanding the relationship between media and decision-making.

You’ve heard that the modern media landscape gives you more direct access to buyers than the days of three TV stations and major newspapers, and that’s true, but legal comes with some interesting limits. Your strategy needs to adapt.

Let me walk you through media’s relationship with buying, the problem with legal media specifically, and how we’re going to fix it.

Media Drives Decisions

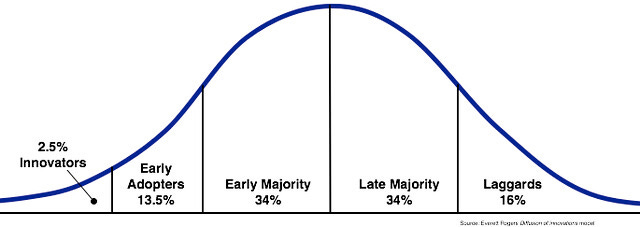

Everett Rogers published his pseudo-biblical Diffusion of Innovations in 1962. He used data to explain how new ideas spread. His work spawned one of the most famous charts in technology circles:

This bell curve illustrates the pace at which most innovations take root: slowly at first, then quickly as a solution gets broad acceptance, and finally teetering off as the market is saturated. Rogers divided the curve to identify certain social roles and how they behave as an innovation spreads.

Applying Rogers’s model, getting the attention of a few legaltech writers and law librarians may be totally reasonable growth for a young company. Groups typically adopt new solutions slowly, then quickly, and Innovators are a good early sign.

But while Rogers’s curve gives the comfort of predictability, it’s often misused to justify strategic indifference rather than patience. This progress doesn’t happen without some preconditions being met, including media presence leading to audience awareness.

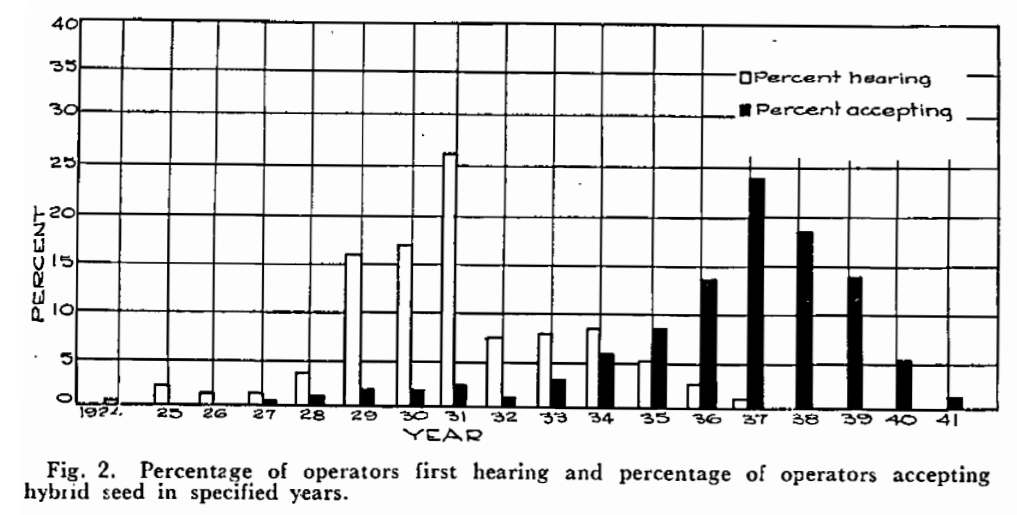

Here’s another chart that Rogers built upon that’s relevant to this conversation:

This figure comes from research on farmers’ very gradual adoption of more productive hybrid corn seed. According to the data, adoption began well after exposure. Only after a significant time lag did the innovation really take off.

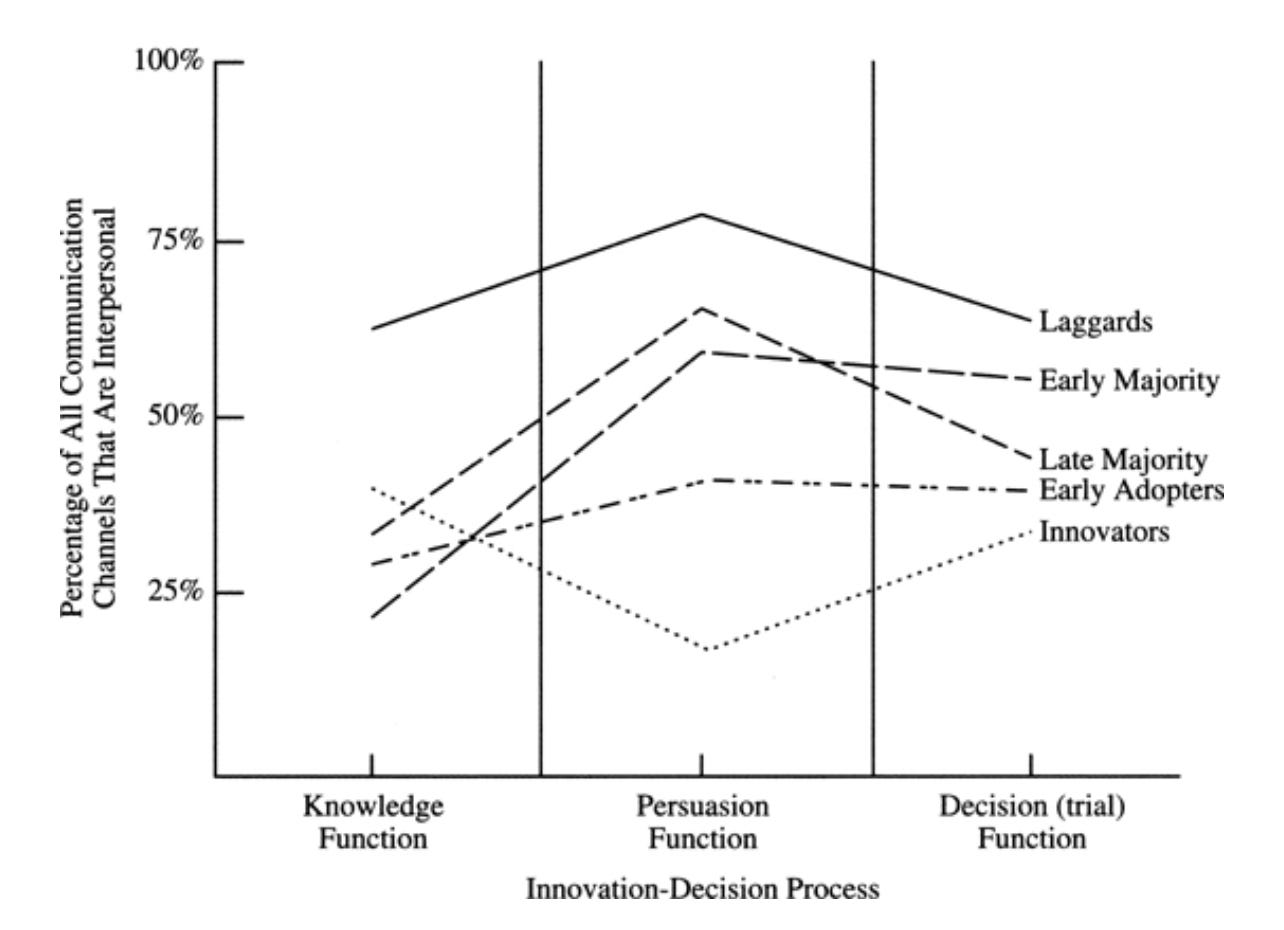

One more chart to set this stage. This one again comes from Rogers’s Diffusion of Innovations. It illustrates who relies on social connections for exposure to new ideas, and how much different roles rely on social pressure to make decisions.

Let’s see if we can underline the takeaway here:

Innovators chase new ideas. They ask around about what people are trying and they consume media. They don’t rely on buddies to make decisions about whether they’ll try an idea because they’re motivated by their status as innovators. They care a lot, but they don’t have much influence on others in the group.

Early Adopters are a bit different. They consume some media and they talk to some Innovators. They don’t wait for everybody else to get on board before they try something, but they don’t jump into craziness, either. This is why everybody else in the group trusts their opinions. Companies win by persuading Early Adopters to try something new then giving them tools to persuade their friends. Reaching Early Adopters is the crucial media game, and we’ll talk about why it’s so tough in law.

Everybody Else. Before we move on, look at the Early Majority, Late Majority, and Laggards. Note that all three rely on the opinions of others to feel persuaded. That’s why the Early Adopters are drivers of awareness and adoption, but not the actual goal. The Early Adopter group is too small to make a market, but you can’t get to the majority without them.

Early Adopters need media to try something, then buddies follow their lead. Geoffrey Moore wrote all about it in his popular book Crossing the Chasm, and I’ll summarize it for you:

Media adapted to social networks. That’s your game.

Yeah, But Legal…

Here’s the thing, though: law is incredibly siloed, and so is our media. We know that’s true and there are good systemic reasons for it.

First, we have jurisdictions and practice areas. Countries, states/provinces, counties, particular courts… Every geographic segmentation is relevant to what we read and who we interact with. And we become subject matter experts over less and less over time. Our media sources narrow as our focus does.

Second, we have an isolating work model. We almost all live in what I call The Churn, which relies on us being butt-in-seat in front of a computer screen for as long as possible. We don’t engage much. Knowledge management in legal is almost entirely focused on what we already know; how we create new knowledge barely gets our attention after the bar exam.

Third, we live in 2022. Media is becoming siloed all over. We seek self-confirmation and it spills over into what we read and who we trust. We’re spending a lot of time in media that’s not relevant to our legal identities and instead use media consumption to reinforce our noisier identities.

The siloed nature of legal media consumption means there are few centralized ways to reach Early Adopters. That makes it difficult to get the ball rolling on adoption, which makes scaled progress in the legal industry incredibly difficult.

To give you an example of the choices this dynamic creates, I remember a debate we had when I worked at a 7-year-old legaltech company. At that age we should have been past the Early Adopter stage and into the Early Majority stage, but brand awareness was low. There had been plenty of positive press and glowing feedback from Innovators, but lawyers’ media habits meant the most socially influential audience wasn’t learning about our solution. So we debated: should we sponsor a legal podcast or sponsor an NPR show, knowing that a tiny portion of that audience would actually be lawyers.

Think about how insane that is. The legal podcast had the target audience of small firm lawyers, but it wasn’t clear they were anything other than tinkering Innovators. Maybe it made more sense to reach the kind of people who are paying attention to professional media platforms like NPR that weren’t focused on law, even if we knew 98% of that spend would be wasted. Maybe that’s where Early Adopters lived???

These are the crappy choices we face in our fractured legal media market.

So What Do We Do?

We aren’t likely to see the rise of any dominant legal media sources soon.

Heck, we already have them. Westlaw and Lexis are obvious behemoths, with ALM and Breaking Media being newer options. But even the winners can’t get into the right minds at scale because the buyers are so siloed. Unless we can all go back 100 years and embed ourselves in law school curricula like the oldest platforms, we have to learn to play a more modern game.

In that, there is good news. The diffusion of innovations doesn’t require centralized media sources, even if that’s easier. As Everett Rogers put it, “Diffusion is the process by which (1) an innovation (2) is communicated through certain channels (3) over time (4) among the members of a social system.”

What matters is how media spreads through social bubbles—the existence of the bubbles is no excuse.

Next week I’ll elaborate on this, but I want to give you the spoiler alert version of how you should solve this problem: creating micro media companies in micro communities, and doing it at scale.

How do you do that? You empower persuasive content creators. You cultivate an atmosphere.

We’ll talk more about that next week.